Any translation mistakes are mine.

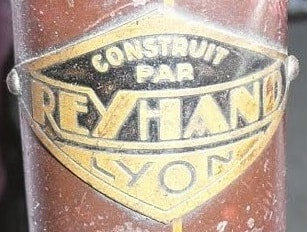

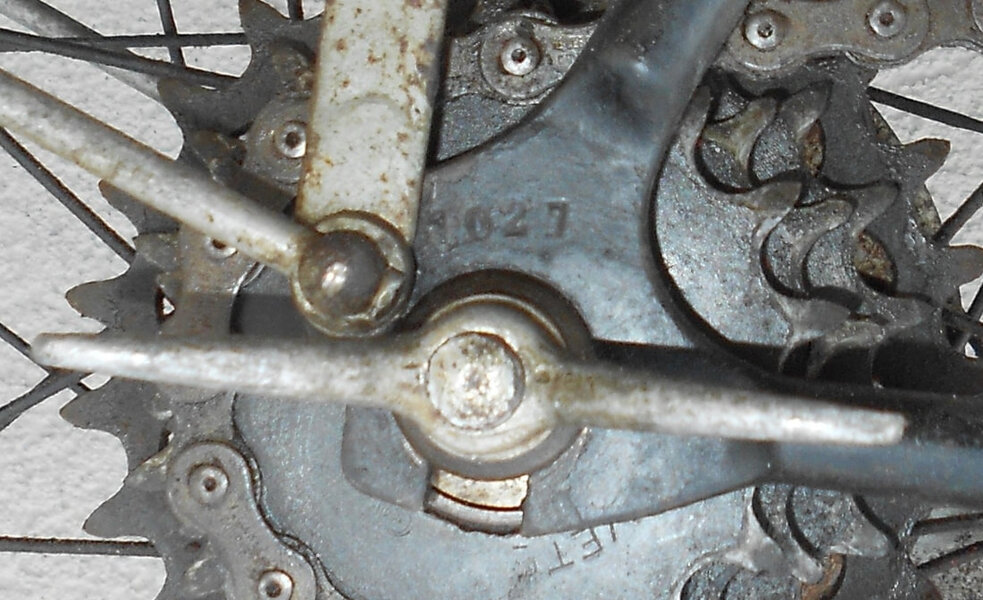

The machine described in the article below still exists. It bears the plaque ‘Built by Reyhand.

No. 1061, it was used by Louis Cointepas until 1983.

Of course it was modernised over the years, but never after he stopped using it.

Here it is today, a precious surviving example.

Here is Louis story of his epic 1935 ride in his own words! Again apologies to any French members.

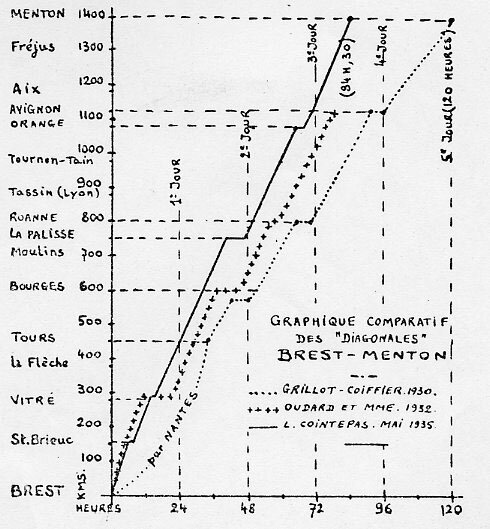

Easter 1930, Grillot-Coiffier completed the first Brest-Menton race in 120 hours, but were delayed by the rain.

Easter 1932, the Oudart tandem left Brest and stopped in Avignon, thwarted by bad weather.

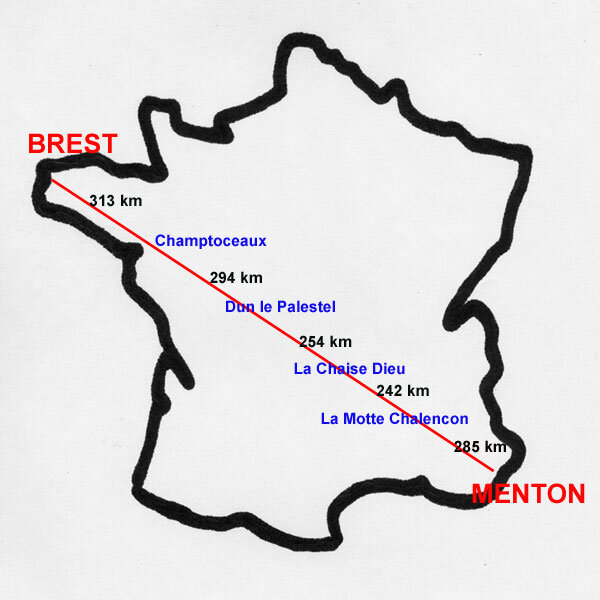

It took more than five years for the Grillot tandem's feat to be beaten. That's enough to show the difficulty of the task, which too few randonneurs have dared to tackle. But there were other diagonals, shorter and still untouched. But Brest-Menton is the most beautiful of all, the one that goes from end to end, the longest route in France, starting from the depths of Brittany, crossing so many different provinces, to end on the jewel that is the Riviera.

The success of such a raid requires a number of favourable conditions: firstly, a trained cyclist, driven by the will and desire to conquer the road and the elements, but not a superman. Then a light, very rigid, very smooth, fairly comfortable machine, which I'll outline at the end of this report. Finally, good weather and a favourable wind. The time of the full moon seems to me to be the most favourable, allowing us to ride at night without lighting and offering a greater chance of good weather.

May or June is the most favourable time, the nights are short and not too cold, the days are not yet too hot, and hikers are not yet tired from too long a season. So, judging all the conditions to be favourable and impatient to set off, I spent a long day on the train from Orléans to Brest, and ended up sleeping in a bathroom in the Hôtel de Paris.

Thursday 16th May. - I leave Brest at 6am, in a drizzle. I know from experience that I have enough for the whole of Brittany and that it rains 300 days a year in Brest. It doesn't matter, because I'm in high spirits, thinking of the sun that awaits me over there in Menton. Coast after coast, finally a long descent, Landerneau, then the road insinuates itself into the hollow of a valley, Morlaix passed without a blow at 9 o'clock. The steep sections became drier and drier, the rain increased, morale dropped and on a long straight stretch lost in the grey sky, I contemplated the failure of the raid. At Guingamp (11.30am) the weather cleared. I have lunch in Saint-Brieuc (1pm): salted butter, dubious food, cider, such is Breton food. I take the wrong route, but I realise it after a kilometre or two. A long descent, after the velodrome, gives me a view of the jade-flecked English Channel. Lamballe (2:30 p.m.) with an interminable reload. After Broons (4 p.m.), there's a downhill section, which is a good 12%. I remember how hard it was to climb it during the Paris-Brest and return trip in 1931.

As I'm following the same route all the way to Laval, I'm not at all bored by the memory of that epic journey. I crossed the bustling city of Rennes along the quays at 6 pm. 15. The hills were over, the weather was fine and I had an excellent dinner in Vitré (8 to 8.30 p.m.). I only ate three restaurant meals during this ride. However, it's important to eat something warm before going into the night, because from 10 p.m. to 7 a.m. you're unlikely to find a café open.

Night comes on gradually, as if reluctantly, but the moonlight allows me to ride without lights: so much strength saved. A coffee in Laval (10.30 p.m.) and I'm back on an unknown road through the Alpes Mancelles. With a quarter of an hour to spare, it took me the same time from Brest to Laval as in 1931.

Friday - I arrived in La Flèche at 2am, an hour ahead of schedule. That's probably why I can't find the people from Mance who were supposed to give me a ride. After searching for a while, I finally find the right direction. Little by little, I fell asleep. Driving at 10 an hour, I swerved on the road; it seemed to me that I was in a second state, allowing me to see the obstacles while sleeping. ‘From the start of a major raid, a separation happens

He no longer hears them, sees them or understands them. His thoughts, gestures and reflexes are focused on a single goal: to succeed. He lives on another plane, in a kind of strange atmosphere, a little miraculous’.

Half asleep, I arrived at Château-Lavallière, where I took a wrong turn. To think that I can no longer spend a night on the road without sleeping and without having the will to react. At this rate of speed, I've lost my hour's head start, as the pace picks up with the day. It's a pity that the Alpes Mancelles are just a name, because the climbs, forcing me to push, would have taken my sleep away. I crossed the Loire at Tours at 6.30 am: Great and beautiful Loire, I'll see you again in Roanne! Immediately after the bridge, I took the road to Amboise, then G.C. 40, which offered the double advantage of avoiding the cobblestones of Tours and the steep slopes of Bléré.

I'm driving through a flat, opulent region, the Garden of France, with its many historic châteaux. Chenonceau, 8.15 am, snack. I head up the Cher valley, an easy route hampered only by a slight headwind. And here comes the classic encounter with the gendarmes: when I tell them that I left Brest yesterday morning to go to Menton, they forget to ask for my number plate. Another classic encounter: the tarmac: for ten kilometres the black, sticky liquid awaits the gravel spread at by the all-too-rare roadmen. I barely made it through, because a few days later, at two other points, I had to navigate for miles on a thick layer of gravel.

A hill broke the monotony of the route, and I arrived in Vierzon at 12 noon. 30. I filled my bag and set off. During this diagonal I ate almost exclusively bread, ham, cheese, jam, chocolate, sugar and orange, washed down with sugar water or coffee for the night. The diet of short, frequent meals worked perfectly for me, with the minimum loss of time. In restaurants, you get away with stopping for at least three quarters of an hour.

Needless to say, the fresh air gives you a ferocious appetite, and when your stomach's working properly, everything's fine.

At Bourges, 14 h. 30, I felt my front tyre deflate; a pump stroke, but 20 kilometres later, I had to replace it. The road to Saincoins is undulating and reminiscent of Brittany. I like the hills, they provide a distraction, but when the distance starts to weigh on me, and the weather is heavy with thunderstorms, I find them rather bad, especially as my knees hurt. Indeed, just before the start, I did a three-day training session in the Morvan, a session which put me on my knees, so to speak, and which the rain in Brittany didn't improve.

After Saincoins (5 p.m.), a long descent takes me over the Allier, while a thunderstorm breaks out further north. At Saint-Pierre I met up with an old acquaintance, the N7, whose twists and turns I knew well and whose course I would follow all the way to Menton. After many kilometres of repairs, I push on along a flat road, because the sooner I get to Lapalisse, the more rest I'll have. In the course of this ride, which I complete at a cyclotourist's pace, this is the only place where I get a bit of exercise. Moulins 7 p.m., refreshments, Varennes passed. Two climbs before Saint-Gérand forced me to take my minimum of 4 m. 60. Finally, I arrived in Lapalisse at 9pm. 50. The first round of 750 kilometres was won without too much fatigue, at an average of nearly 19. At that pace, I could have reached Menton in 80 hours.

Saturday. - At 4.30 a.m. I wake to the gentle murmur(!) of water trickling down the gutters. As soon as I was dressed, I noticed that snow was falling in May. To make matters worse, my rear tyre was flat. I re-inflated it and set off at 5.30am, stoically, in the snow, because I had to meet Lucien Clairet at 7am in Roanne. After a few kilometres on a gentle slope, I was blinded, frozen, drenched in sweat and soaked through with snow falling in tight flakes. It piled up in my mudguards, blocking the wheels and piling up in the crankset and around the hubs. It now forms a five-centimetre layer in which I slip and slide. And my rear wheel is still flat. I broke down at the Café du Sud, in Saint-Martin, where I was refused a hot brick and the right to dry off by the cooker. I was clearly considering the failure of the raid. Can you imagine setting off in weather like this? If I'd stayed in bed two more hours, I could have avoided this ordeal.

At 7.45am, the snow having stopped, I set off in an unspeakable cesspit, driven by a northerly wind, while the surrounding hills put on their winter finery. I soon found Mr Caillot, from the G.M.R., who had come to meet me despite the snow. We chat cheerfully together, as it's the first conversation I've had since Brest. We arrive in Roanne at 9 o'clock. Telegram to Lyon announcing my arrival at 1pm. 30 only, grease the bike, which needs it after the snow, and have a snack. At 9.30 we set off again, then Mr Caillot leaves me at Saint-Svmphorien.

Aided by an almost favourable wind, I climbed easily, whereas at Easter, the gusts from the south had us pinned down. Pin-Bouchin, the highest point of my diagonal, was reached at 11am. A bust of Napoleon recalls his many visits to this spot. This great general understood, like Caesar, that the road, enabling armies to move quickly, was a significant factor in victory.

A quick descent takes me to Tarare for refreshments. A series of familiar steep climbs and I'm in Tassin at 1pm. 30.

And here's Mr Reiss on his tandem. It's a pleasure and a morale booster to find people you know. Pessimistically, he tells me that there will be a strong S-S-W wind in the Rhône valley. We took G.C. 13 bis, well known to hikers, which was shorter and avoided the cobblestones of Lyon and the steep slopes of Saint-Symphorien. The ‘Comet’ tandem went into action, it was a 40 and I was taken off in the wheel. At this speed, we soon reached Briguais, at the same time as the rain. Given the inclement weather, Mr Reiss returned to Lyon, having entrusted me with an extra-light hose.

A few minutes later, a hailstorm of rare violence forced me to take shelter: the hailstones were collected with shovels. The wind was quite annoying and slowed my pace. Along the way, I picked a few cherries from the trees. Like Velocio, I cross the Rhône at Saint-Vallier. On the N7, the wind caught me head-on and I was dropped by the Rhodania, travelling down the river at 25 an hour. I understood and, at Tain-Tournon (6 p.m.), I took the N. 86 again. This route, which follows the foothills of the Ardèche as closely as possible, is better sheltered from the wind and less crowded with cars than the N. 7. It is also more picturesque and is to be recommended to cycle tourists descending into Provence.

I have dinner in Cruas (8.20-9pm), a small village with a large cement factory. Although the wind had died down, the pace was slow, as I didn't reach Pont-Saint-Esprit until midnight. This village is a strategic point for the Grands Raids. It's where I crossed the Rhône during Paris-Nîmes and Strasbourg-Cerbère, two nasty stages completed at an average speed of 20. Today, the speed is slower, but the distance is longer and the weather less favourable.

Sunday - Immediately after the bridge, a short V.O. takes me to Mondragon. And here again is the N7 in all its night-time splendour, where lorries, the behemoths of the road, are king. I fall asleep again, but not without danger on this busy road. ‘There comes a time when the mind falls asleep, the brain no longer reacts, numbness dominates the reflexes, man is no more than a wreck obeying his instinct to lie down like an animal because he can't take it any more. The remedy would be the presence of a companion to provide a diversion, or to go for it, to push as hard as you can; but at that point the will is absent. Anyway, in Orange, I lay down like an animal in an abandoned lorry.

For two hours I slept, lulled by the roar of the lorries, but woken by the cold. I walk up the hill to warm up and I dread the icy descent to Courtheron.

At Le Pontet (4.30 am), I take a shortcut to avoid the cobbles of Avignon. As dawn broke, the cold became more intense: I was pierced, frozen all over. Oh, sweet Provence, you're just a name! And not a single café open before Lambesc. Two cyclists caught up with me, just as cold as I was. I let them go, knowing from experience what it costs to breathe in oil fumes. The road is flat, then begins to undulate before Lambesc (7 a.m.), the country that proved fatal for Lemal on the Dunkerque-Menton trip.

I was overtaken again by a cyclist; with the sun, the pace had picked up and we were riding at a good pace, delayed by an untimely puncture; you wouldn't think of setting off on such a raid with old hoses. I put the punctured tube back together in Bourges. Lunch in Aix (8 a.m.). I set off all the better as a westerly wind had picked up and would increase during the day. As pleasure never comes alone, I met a cyclotourist who had come to meet me, alerted by Mr Reiss. We've never seen each other before, yet we recognise each other. As we rode along at a good pace, we noticed the excellent performance of the CAR hubs we both own. I stopped to refill my hose. A long straight descent takes us to Saint-Maximin. At Tourves, my companion leaves me to return to Aubagne. Shortly afterwards, with my hose still deflated, I took the super-light up to Mr Reiss. What did I do there? Pushed by the wind, I flew away, literally surprised by this unexpected performance, pushing my 7 m. 70 smoothly. Brignoles, 10.45 a.m., refuelling; I set off again in aerobatics, as the sun was heating up hard between the houses. I catch up with a lorry, whose infernal noise reminds me of its passage through Orange. We have an epic duel: I let it go on the uphills and downhills; it loses me on the flat, because its din prevents me from sticking to it. At this pace, I'm in Fréjus by 1.30pm. It's sunny, the cerulean sea seen to starboard, palm trees, roses, flowers, the Midi: come on, life is beautiful. Amid the maritime pines, the road gradually rises. It culminates 11 kilometres from Fréjus, a small pass reached in 40 minutes. This is the plunge into Cannes, a plunge cut by counter-slopes in an enchanting setting. I avoid the cobblestones by taking the seaside road to the port of Cannes (3 pm), crowded with boats. Passing through lush vegetation, I pass Antibes. Now the plain is barren, and there are as many cars as in Paris. After the Var bridge, I take the coastal road. Horror, the wind has just turned east. In the streets of Nice (4.30 p.m.), sheltered by the houses, I went to see Mr Barnols, a cyclotourist with a legendary warm welcome, who was unfortunately absent on this Sunday.

I'm riding back down the Promenade des Anglais, which is packed with people, when I see a cyclist adjusting his handlebars, and what a cyclist: Griffon, who I thought was a hundred miles away. I had no trouble getting him to Menton for the final check. But he was no longer in shape, as he had just arrived from Corsica, the wind was blowing from the front, hill after hill, and we lost our way in Monte-Carlo. One last hill, a long descent and we finally arrived in Menton at 6.30pm

Menton, supreme hope and supreme thought, for which I have faced and overcome the elements and which I have been thinking about for 1,400 kilometres, since 84 h. 30m

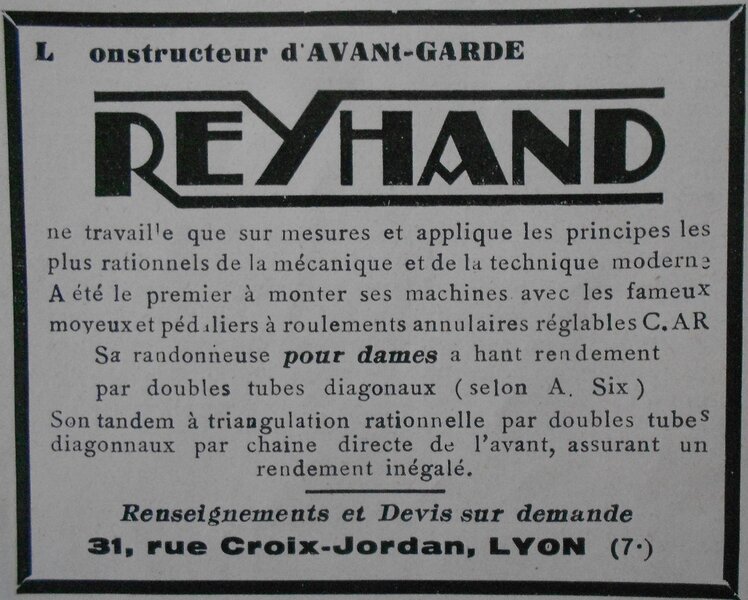

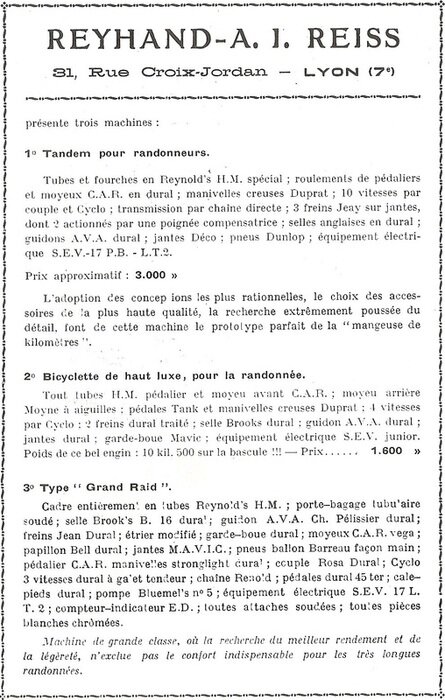

An hour's rest and back to Nice, awaiting the return to my hometown via the Napoleon route, another 875 kilometres. In other words, this diagonal didn't tire me at all. That's down to the perfection, comfort, rigidity and exceptional performance of my bike: Reyhand frame in Reynold's H.M. tubes, all accessories in dural, CAR bearings. And always a Cyclo-Tank, 4 speeds, the king of derailleurs. That's what makes me say that with such a machine and such bearings I no longer deserve any credit for what I've just achieved.

I would like to thank Messrs Reiss, Ripet and Raimond, as well as the all too rare friends I met along the way.

This machine, a prototype weighing 10 kg 500, has now covered 5,000 kilometres without the slightest problem. Who said that dural couldn't take the strain?

Can we do better? A well-trained hiker on a good machine, with wind and good weather, will clock up 70 hours, or an average of 20.

This is still a long way from Opperman's 57 hours over the 1,350 kilometres of the English diagonal, but we forget that he is a professional rider who has time to train, who is looked after and encouraged by a support team that provides him with food, drink, clothes and wheels, and whose presence is a physical and moral encouragement. When a French randonneur sets off in the same conditions, he will do Brest-Menton in 60 hours. The less time you spend in the saddle, the faster you go; that's just two nights on the road that you can spend without sleeping.

Who will be the first to conquer the record for the longest route in France?

Louis COINTEPAS, 4-6-35.

So what did he ride?......Note the "seat post"